Incorporating Culture into a Language Classroom throughChinese Character Teaching and Practice

Incorporating Culture into a Language Classroom through

Chinese Character Teaching and Practice

Ming Wu

Department of Classical and Modern Languages, University of Lousville

Authors Note

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Ming Wu, Department of Classical and Modern Languages, University of Louisville, Louisville, KY 40292

Contact: ming.wu@louisville.edu

Abstract

Acquiring Chinese characters is essential for improving students’ overall Chinese language proficiency. However, American students often feel intimidated when it comes to reading and writing Chinese characters. This paper introduces a comprehensive approach and provides Teaching Chinese as a Second Language (TCSL) teachers with specific strategies for incorporating culture into Chinese character teaching and practicing activities. The author points out that incorporating cultural elements into teaching helps to build the three-way connections between the shape, meaning(s), and pronunciation(s) of a Chinese character. Through stories, pictures, animations, video clips, and hands-on activities, students are introduced to a fun, engaging, and effective way to master Chinese characters as well as exposed to the fascinating culture and wisdom of ancient Chinese as conveyed by the unique writing system. This approach also nurtures students’ interest in learning and practicing Chinese characters through poetry and artwork, brings their attention to the close connections between characters and phrases, and leads to a deeper understanding of Chinese language and culture.

Keywords: Teaching Chinese as a Second Language; Chinese characters; Chinese culture; language and culture

Introduction

In world language classrooms, it has become common sense that language and culture are inseparable. Language is a vehicle that carries and expresses culture. Understanding of the target culture will significantly improve learners’ sociocultural competence and cross-cultural communication skills. Brown (2014) described the relationship between language and culture as follows:

It is apparent that culture, as an ingrained set of behaviors and modes of perception, becomes highly important in the learning of a second language. A language is a part of a culture, and a culture is a part of a language: the two are intricately interwoven so that one cannot separate the two without losing the significance of either language or culture. The acquisition of a second language, except for specialized, instrumental acquisition (as may be the case, say, in acquiring a reading knowledge of a language for examining scientific texts), is also the acquisition of a second culture. (p. 171)

Note. The image of ancient bamboo strips is from http://www.sohu.com/a/135462830_523099

The images showing the evolution of 册 are from 字源网

http://qiyuan.chaziwang.com/etymology-20513.html

Figure 2

An image showing a man scraping characters off of bamboo strips

Note. This image is from https://www.zhihu.com/question/41739911?sort=created&page=1

The original picture was a screenshot from the 2017 Chinese TV drama The Advisors’ Alliance (Part 1).

Properly incorporating cultural elements through etymology into Chinese character teaching can also help to distinguish characters that confuse students, such as 天 versus 夫, 高 versus 亮, 目 versus 日, 既 versus 即, and 见 versus 贝. For example, if students cannot tell the difference between 天 (sky, day, heaven) and 夫 (adult male, a married man, husband), the instructor can introduce the ancient Chinese capping ceremony, show related pictures or video clips, and explain that, during this ceremony, a male’s hair was bound with a clasp and capped to suggest the beginning of his adulthood. The “sticking-out cap” on 夫 is what makes it look different from 天. An image of a man wearing traditional Hanfu costume and a cap on his head while opening his arms wide will give students a strong visual impression. Teachers could even invite students to wear a Hanfu cap and imitate the character 夫 with their body language. This type of act-it-out cultural activity is a fun and engaging process to help students discern the differences between characters.

Figure 3

A PowerPoint slide showing the evolution of the character 夫 and the capping ceremony.

Make it stand out

Note. The image showing the ancient capping ceremony is from https://baike.baidu.com/item/%E5%86%A0%E7%A4%BC/816971. The etymology images are from http://qiyuan.chaziwang.com/etymology-5450.html

For some Chinese characters, although their original meanings remain, it is difficult for a second language learner to draw connections between the now very abstract shape and its original meaning. For example, the character 心 represents “heart,” which originated from the pictogram of a heart. However, the modern shape of 心 does not quite look like a heart. In this case, teachers can adapt or even create a more intuitive image to help build the connection.

Figure 4

A PowerPoint slide created by the author to connect the character 心 with its meaning “heart.”

Bringing Art into the Language Classroom through Character Learning Activities

Practicing the writing of Chinese characters should not entail mere mechanical copying of them in the right stroke orders. Chinese characters are naturally in connection with visual art, such as calligraphy. Calligraphy is the art of beautiful handwriting. Many teachers treat it as an extracurricular cultural activity. They give students limited opportunities to try calligraphy with traditional writing brushes, rice paper, and ink. This kind of activity can be intriguing at the beginning, but it can also be problematic because 1) the preparatory work for writing with brush and ink takes a great deal of time and sometimes becomes very messy, and 2) students can become frustrated quickly because of how difficult it is for beginners to use traditional calligraphy tools.

Bringing visual art into the language classroom can go beyond traditional calligraphy with writing brushes. Teachers should observe student reactions closely and adjust strategies according to feedback. In contemporary China, calligraphy with a pen is also very popular. A pen or even a pencil can be used to produce inspiring calligraphy art pieces as well. During the COVID-19 pandemic, some Chinese calligraphers shifted to online teaching and produced high-quality instructional video clips, such as Zhi Xing Calligraphy School’s recorded demonstrations of calligraphy with pencils. This variant of Chinese calligraphy is closer to American students’ reality and easier to implement.

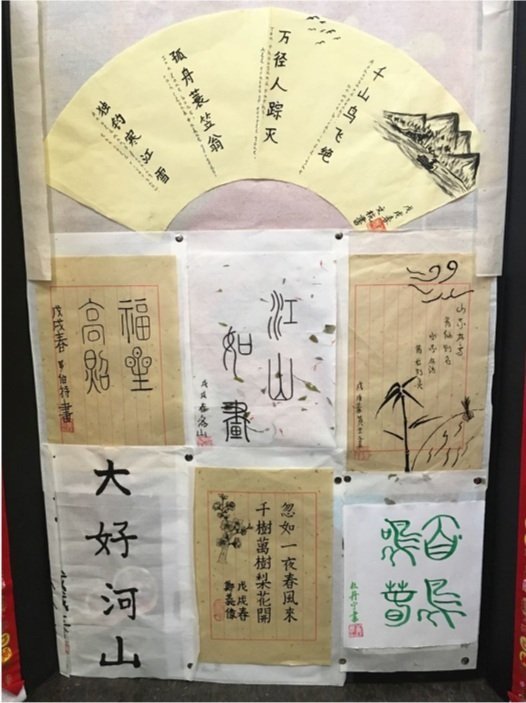

Other than considering different choices of writing tools, teachers should also ask themselves this question: Is writing the standard script the only option when bringing Chinese calligraphy into character teaching? The truth is that, when given freedom to choose their own styles, writing tools and surfaces, students are more engaged, focused, and creative. They can produce beautiful character artworks on rice paper, card stock, blank bookmarks, blank red envelopes, fans, umbrellas, and pottery. In the largest Chinese teachers’ online community on Facebook, Lin (2021) even shared her lesson plan for teaching students how to make their own Chinese seals with craft foam sheets, which are easy to find and very affordable in the US. Bringing visual art into the classroom ignites students’ passion for practicing character writing.

Figure 5

University of Louisville Student Atticus Card’s calligraphy art (2019): An ancient Chinese poem on a paper umbrella

Figure 6

University of Louisville students’ artworks in various scripts, produced with different writing tools on a variety of surfaces.

It is not only traditional Chinese art that can be incorporated into character teaching and practice: Various other art forms can also be utilized to stimulate student interest in learning. When the character 米 (rice) is taught, students can be encouraged to make their own character art by arranging grains of rice in the shape of the character. Yan Huang created a website to show her and her students’ creations of Chinese character art. Her approach involves encouraging students to draw pictures based on their own understanding of a specific Chinese character. This method is highly successful in her K-12 classrooms and has been implemented by several other teachers.

Figure 7

Character 米 (rice) art with grains of rice by the author.

Figure 8

Middle school students’ creations of Chinese character art.

Make it stand out

Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.

Note. Chinese teacher Zhigang Liu tried Yan Huang’s approach. His middle school students created these character artworks in 2019. Zhigang Liu owns the copyrights for these photos.

Chinese folk art can also be used to integrate culture with character learning. Chinese characters with vertical symmetry features are perfect for papercutting designs. During the Spring Festival celebration, a hands-on 3D 春 (spring) papercutting activity can give students a deeper impression of the structure and meaning of this character. They will also be exposed to China’s papercutting folk art, which has a history spanning 2000 years. In recent years, realizing the value of papercutting in classrooms, several teachers and organizations have designed new papercutting patterns around traditional festivals and have shared them through social media. For example, Taipei Confucius Temple has been sharing their new modern papercutting designs frequently through their Facebook Fans’ Club page during major traditional Chinese festivals. These designs are often perfect combinations of Chinese characters and vivid patterns of flowers or animals. Chinese language teachers around the world can access these designs for free and use them in classroom teaching. The need for incorporating culture into a language classroom also has a positive impact on reviving and preserving traditional Chinese culture. It even plays a role in modernizing traditional folk art, such as papercutting.

Figure 9

2022 Spring Festival “Year of the Tiger” Papercutting Design 春虎 (Spring Tiger). Shared by Taipei Confucius Temple on January 22, 2022.

t

Note. The copyright for this image belongs to the Taipei Confucius Temple. https://www.facebook.com/taipeiconfuciustemple/photos/pcb.4819375478114302/4819117584806758/

Some professionally made masterpieces of animation loaded with cultural elements are also great resources to boost students’ interest in learning Chinese characters. One is called the Story of 36 Chinese Characters, which is a remarkable animated short film that shows the formation of basic Chinese characters. It consists of a brush painting in motion accompanied by traditional music.

Even emojis, an important element of pop culture, can be used in character teaching. In recent years, oracle bone script emojis have been trending in China. According to Ying (2018, para. 2), “the emojis use the oracle bone script to illustrate online buzzwords and internet slang. They combine the pictographic nature of the characters found on ancient ‘oracle’ bones with color and animation.” These oracle bone scripts with a modern twist are perfect examples to show how traditional and modern Chinese culture are bound together by Chinese characters.

Figure 10

Examples of oracle bone script emojis.

Note. The image is from an article introducing oracle bone script emojis on Sohu.com. http://www.sohu.com/a/218591510_162522

Incorporating Culturally Rich Idioms and Ancient Chinese Literature into Character Learning

Do students need a high Chinese proficiency before they start learning and understanding idioms and ancient literature? The answer is “no” if their method of learning Chinese characters is correct. Kecskes and Sun (2017, p. 127) introduced “character-unit” theory and “word-unit” theory in their book, as follows:

The main tendency in Chinese as a Foreign Language (CFL) teaching is to assume that the word is the basic lexical unit, as confirmed by the vast majority of handbooks available. This approach is regarded as representative of the tradition in pedagogical studies and is responsible for relegating vocabulary instruction to a marginal position compared to grammar. Nevertheless, it is worth mentioning that a debate, which started in the 1990s, has increasingly focused on the opposition between the so-called character-unit (zìběnwèi) theory and the word-unit (cíběnwèi) theory, with a number of Chinese scholars supporting the idea that, as the convergence of the phonetic, semantic, lexical, and grammatical levels, character, rather than word, should be considered the basic unit of analysis (and of vocabulary teaching).

Modern Mandarin Chinese vocabulary is primarily composed of compound words made up of two or more morphemes. Each morpheme is recorded by one character and pronounced in one syllable. Therefore, modern Mandarin has more disyllabic words. Conversely, disyllabic words rarely appear in ancient Chinese literature. Classical Chinese is based on single morpheme words recorded by only one character. On this basis, culturally rich idioms and ancient Chinese literature, especially poetry, can be integrated into character teaching if the classes are carefully designed. Seeing characters in meaningful and beautiful literary works will also make acquiring them and memorizing them easier and more fun. For example, at the beginner level, right after learning the basic characters 一 (one), 二 (two), 石 (stone, rock), and 鸟 (bird), teachers can use the simple idiom 一石二鸟 (kill two birds with one stone), which also has an English equivalent, to tie the characters together and raise students’ interest.

For intermediate and advanced level students, an even more important step is to help them recognize the meanings of characters in compound words and help them realize that what they assume are “fixed” structures are actually combinations of detachable and reusable characters. For example, when students study the word 新闻 (news) at the intermediate level, most textbooks do not divide this word and explain the meaning of each character. Teachers should step in and point out that 新 is “new” and 闻 actually means “to hear.” When 闻 is used alone in modern Mandarin, the meaning is very often “to smell.” However, its original meaning, “to hear,” still remains in more than 30 compound words and idioms, such as 见闻 (what one sees and hears; knowledge), 举世闻名 (the whole world has heard its name; be known to all the world), and 百闻不如一见 (hearing one hundred times is not as good as seeing it once; seeing is believing). One of the greatest ancient Chinese poems, 春晓 (“Spring Dawn”) by the renowned Tang Dynasty poet 孟浩然 (Meng Haoran) can also be integrated into the teaching of 闻. The full poem, with Shawn Powrie’s 2015 translation, is quoted below:

春晓 Spring Dawn

春眠不觉晓, Sleeping in on a spring morn — sensing not the dawn,

处处闻啼鸟, Everywhere is heard the tweeting of the bird,

夜来风雨声, Come night and the wind-rain sound,

花落知多少. Unknown how many petals fell to the ground.

The character 闻(to hear) itself actually originated from the combination of 門 (door) as its phonetic component and 耳(ear) as its semantic component. Analysis of the formation of characters and their functions in compound words, idioms, and ancient literary works can help to connect the shapes with meanings and bridge modern Mandarin and Classical Chinese. In fact, for advanced level students, this is an easy path to the accumulation of more idiomatic terms, which is necessary for improving their language proficiency to the Superior level described in the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (ACTFL) Proficiency Guidelines (2012).

Conclusions and Future Study

Learning Chinese characters does not need to be painful. The process can be fun, inspiring, and engaging when proper cultural elements are included in teaching. Incorporating culture into a Chinese language classroom is a win-win strategy. Students are exposed to the fascinating culture and the wisdom of ancient Chinese as carried by the unique writing system. Cultural elements help to motivate students and accelerate language acquisition.

This method also nurtures students’ interest in learning and practicing Chinese characters through poetry and artwork, draws their attention to the close connections between characters and phrases, and leads to a deeper understanding of the Chinese language and culture. However, currently, bringing culture into Chinese character teaching still depends on individual teachers’ efforts. Limited time, energy, and resources dictate why this effective approach is not yet widely adopted in world language classrooms. Future research should focus on building the much-needed supporting resources, such as a database with accurate cultural information carried by every character and details about proper teaching methods.

References

American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages. (2012). ACTFL proficiency guidelines. Hastings-on-Hudson, NY:

American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages.

Brown, H. D. (2014). Principles of language learning and teaching (5th ed.). White Plains, NY: Pearson Education.

Chen, G. (2018). Integrating culture into beginner-level Chinese language teaching. Journal of Foreign Languages and Cultures, 2 (2), 94—103.

Kecskes, I. & Sun, C. (2017). Key Issues in Chinese as a Second Language Research. New York, NY: Routledge

Lin, H. C. (2021, November 29) How to Make Chinese Seals out of Foam Sheets.

https://www.facebook.com/groups/1591925434230401/permalink/4584301084992806/

Ying, G. (2018, March 3) Giving a modern twist to the oracle bone script. China Daily.

https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201803/07/WS5a9f344fa3106e7dcc13fff9.html

Yu, L. (2009) Where is Culture? Culture Instruction and the Foreign Language Textbook. Journal of the Chinese Language Teachers

Association, 44 (3), 73-108.