Listening to Our Learners: A Thematic Analysis of U.S. College Students' Preferences in Language Education Resources

Listening to Our Learners: A Thematic Analysis of U.S. College Students' Preferences in

Language Education Resources

Giovanni Zimotti, 1 Rachel A. Klevar, 1 Gabriela Olivares-Cuhat, 2 Eden G. Jones3

1 Department of Spanish and Portuguese, University of Iowa

2 Department of Languages and Literatures, University of Northern Iowa

3 Office of Teaching, Learning, and Technology, University of Iowa

Author Note

We have no known conflict of interest to disclose.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Giovanni Zimotti at giovanni-zimotti@uiowa.edu

Abstract

Commercial language textbooks are utilized by many professionals in higher education. Unfortunately, these second language learning textbooks are prepared without direct input from their users, are primarily based on stories of fictional characters, and may not always relate to the reality of the student population. Due to this situation, this article describes a project which aims to find out what content interests U.S. college students to design an open educational resource that is more inclusive and relatable to the learning needs and lives of our students. To this end, 283 students provided feedback through an online questionnaire. The thematic analysis of the responses indicate that students view language learning as a process of intercultural discovery, value the understanding of different cultures, and are interested in social justice topics. The article concludes by giving pedagogical recommendations for the creation and adoption of OERs best suited to meet the needs of a diverse student population.

Keywords: Open Educational Resources, language textbooks, language topics

Introduction

Over the past two decades, there has been an emergence of more affordable alternatives to textbook publishing than the traditional commercial textbooks from established companies. These alternatives use Creative Common licenses that allow instructors to freely adopt, share, and modify these pedagogical resources which are commonly known as Open Educational Resources (OER). However, while teachers and scholars have a wide range of free resources at their disposal, the process of promoting and implementing these materials has proven to be slow. For example, even as late as 2012 a faculty and administrator survey in Florida reported that more than half of respondents “were ‘not at all familiar’ with open access textbooks” (Morris-Babb & Henderson, 2012, p. 151). While the adoption of this resource has increased since the early 2000s, many instructors remain unaware of their existence and pedagogical benefits.

There has, however, been a marked increase in research on the effectiveness of OERs as learning materials, including direct comparisons between OER and commercial textbooks. For instance, studies have found that OERs are perceived to provide content on par with that of commercial textbooks (Hilton, 2019), their cost-effectiveness enhances student learning outcomes (Hilton, 2016), and their usage is associated with improved academic performance and reduced course drop-out rates (Colvard et al., 2018; Clinton & Khan, 2019).

OER textbooks allow instructors to tailor the content of their offerings to the needs of their students, both financially and pedagogically. They also provide authors with the flexibility to create materials for specific instructors’ needs. Moreover, OER textbooks provide an unparalleled opportunity for authors to adapt and modify their work according to the diverse needs of various educators.

The creation and use of OERs has attracted increasing interest in the field of L2. A significant number of Spanish OERs released in recent years support this trend, as shown in Appendix A. To better meet the unique needs of our students, the goal was to create an OER Elementary Spanish textbook specifically designed to address the reality of our students. We decided to consider their backgrounds, interests, and previous experiences learning Spanish. With this in mind, we provided students with a survey in order to collect their perceptions of their current textbook, thoughts and opinions on topics of interest and suggestions for improvements.

In addition, we aimed at creating a community of language learners through topics that genuinely interest students and trigger an intrinsic motivation to learn an L2 while making the learning process more enjoyable and meaningful (Gardner, 2010).

Also, by involving students in the early development of a textbook and considering their feedback, we believe we made them feel like active members of the L2 community, an idea supported by Bernaus (2010), who stated that students “will be more motivated to engage in a task if they have some say in what the task is” (p. 186). Moreover, when students envision themselves as active members of a community or classroom, they are more motivated to direct their language learning process and achieve effective communication (Dörnyei, 2009)

On the other hand, few studies have analyzed the type of content of L2 commercial textbooks from different points of view. For example, Siegel (2014) looked at the authenticity of the topics of a textbook for Japanese learners of English and concluded that more authentic topics were needed to “better prepare students for the world out there” (p. 363). Other researchers have focused on the role of gender (Korell, 2021; Robles, 2007) and cultural representation (Hilliard, 2014) in L2 textbooks. Robles (2007) reported that women were underrepresented and were portrayed executing stereotypical activities assigned to women while never in roles such as firewomen, lawyers, directive jobs, etc. Additionally, in textbooks published by Spanish companies, women from Latino countries and the U.S. were usually left out (Robles, 2007). Hilliard (2014) stated that there was an underrepresentation of minority groups and cultures in images and listening activities. In her analysis, Korell (2021) showed that, while some progress has been made (e.g., textbooks assign less stereotypical roles to women), textbooks “still contribute in a subtle way to the social construction of gender inequality” (p. 219). Thus, gender is still presented as a binary norm, there is no inclusion of LGBTQ+ people, and gender-neutral language is absent from advanced language textbooks.

On the other hand, the presentation of culture in OER textbooks was discussed by McKay (2003), who recognized the importance of incorporating the local culture into L2 learning to facilitate interactions. Using an OER framework for the dissemination of quality educational information is an act of social justice since it provides free access to an otherwise inaccessible content. It is important to remove the substantial barriers that book purchases bring to a vast majority of students, a fact that is exacerbated among historically underrepresented college students (Jenkins et al., 2020). What is more, OERs should ensure that students see themselves reflected and enfranchised in the coursework (Seiferle-Valencia, 2020) through explicit representations and perspectives which include antiracist, antisexist, queer, and those from marginalized groups. Therefore, creating an OER textbook through a process-centric approach that queries students about content rather than imposing it, was considered a main tenet of this project as it “will foreground the value of diverse opinions'' (Bali et al., 2020, p. 2).

To address these issues, our study was guided by the following research question: In what ways can a Spanish OER address the L2 interests/needs of our diverse student population?

Methods

This project stems from an online survey given to college students in order to provide feedback on their learning practices and preferences. The idea behind this approach was to put participation and action research at the forefront of education. The researchers’ concern was to give students a voice to create a learning resource based on their needs and wants. The data gathered was used to guide the book creation and activities.

The Context of the Project

This study was conducted at a large public R1 institution in the U.S. and an online questionnaire was distributed to all students enrolled in courses in the Spanish Basic Program. The program is structured as a four-semester sequence, which, upon completion, allows students to fulfill the general education requirement for World Languages. True beginners start by taking Elementary Spanish I, while other students are enrolled in language classes according to the scores obtained in language placement test. By the end of the fourth semester, students are expected to reach a minimum of Intermediate level of proficiency (ACTFL) in the target language, although many of them go beyond that level.

When the questionnaire was distributed, the program was using a flipped, or hybrid, approach, in which students were introduced to new language concepts through online activities outside of the class time. By utilizing this flipped approach, students were able to work at their own pace by watching pre-recorded video lectures and completing daily online activities included in the publisher’s learning platform. When students returned to the class, they engaged in a range of communicative activities aimed at developing language skills and intercultural competence, without explicit focus on grammar. In this manner, most of the class time was devoted to the fostering of oral communication while a small portion of the class-time was dedicated to teacher-guided clarifications of difficult concepts. At the time of the project, the Spanish program relied on a commercial textbook called Protagonistas (Cuadrado et al., 2018), which was based on a communicative approach and emphasized “task-driven communication within meaningful, pragmatic contexts of everyday life.” (Cuadrado et al., 2018, p. IAE-5).

Participants

283 students attending a large U.S. research university participated in the study, which followed IRB protocol. All participants were enrolled in a required general education course as part of a language requirement. All students enrolled in one of the four elementary and intermediate levels of Spanish were invited to participate and received a link via email to complete a survey voluntarily. The majority of the students’ ages ranged from 18-21 (n = 243) and only 20.5% (n = 58) identified themselves as being part of an underrepresented group. In this latter division, the most representative category selected was “Two or more races”, and the second most representative responses were “Hispanic/Latino” and “African American.” In addition, first-generation students were also represented and comprised 23.32% (n = 66) of the sample.

Tools

An online questionnaire created using the software Qualtrics was used to collect information. Demographic questions were used to gather information which included questions about age, minority group, and first-generation status based on a belief that all voices should be included in this exercise. The remaining five open-ended questions inquired about topics that students liked or disliked and future topics of interest, which were further examined via Taguette, a free and open tool that allows researchers to codify qualitative data in order to find common patterns (See Appendix B).

Data Analysis

First, the questions regarding the participants’ demographics were tabulated and are provided in the participant section of this article (see above). Then an inquiry was conducted by means of a thematic analysis through implementation of Taguette-a text tagging tool to start a coding process. After removing the answers from the participants who did not complete the qualitative part of the survey, we were left with 1130 responses to the five open-ended questions out of 283 participants.

The analysis of the open-ended responses involved a line-by-line coding process, which facilitated the grouping of distinct categories and themes as proposed by Charmaz in 2006. In this process, an initial coding was done by the team leader, who then presented the analysis to the research team. In this second phase, the investigators discussed the pre-identified themes and categories to reach consensus. In case of disagreements, the team engaged in discussions until a mutually agreed-upon resolution was found.

Findings

While coding the answers, we observed that some major themes emerged from our students' voices. The emergence of these themes reshaped our research goal towards identifying which topics ought to be included in our textbook leading to a broader and more compelling analysis. This study grouped the themes that emerged during the coding procedures into four main categories. We first focused on why our students are learning a language. Then, we discussed the topics that most or least interest them, which was the initial goal of this study. The third topic addressed the importance of introducing social justice themes, such as inclusive language in the Spanish classroom. We ended this analysis with an evaluation of the value students assigned to their teachers and to language-learning tools.

Why Are Students Learning a Language?

The answer to this question was not part of our initial purpose; we wanted to get information about the topics that most excited our students. However, the majority of students took the opportunity to tell us why they were learning a language. We were pleasantly surprised by this outcome, since their responses provided a snapshot of the motivations behind their learning. When analyzing the results, it is important to underscore that most of the participants were taking a Spanish course as part of a university language requirement. Therefore, we were pleased to find only four students who expressed dissatisfaction with being required to take a language class. For example, one student said that he “hated this course”, while another said that he had “no passion or interest in this language.”

Besides the responses of the few students who did not show interest in learning a language, three main types of themes emerged from the analysis of our students’ opinions. The largest group, which we define as intercultural discovery (n = 68), included students who were excited and motivated by the possibility of learning about different cultures, traditions, and communities in a Spanish classroom. The second group, identified as language learning, includes all the responses that demonstrate our students’ enthusiasm about gaining the ability to communicate with other Spanish speakers. The third group, labeled personal challenge, is smaller but not less important. The group consists of students who viewed learning a new language as a task they were eager to tackle. The hierarchical framework of all the tokens identified for this section is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Hierarchical Framework of All Tokens Regarding the Reasons Why Students Are Learning a Language.

One main finding is that undergraduate students indicated a willingness to learn about the heritage, culture, and traditions of Spanish speakers who reside in the US. Many students said that what excited them the most “in a language is learning about other cultures.” Another participant further explained by saying that what was most appealing to them consisted of “being able to expand my horizons and absorb as much of another culture as possible.” This willingness to learn about other cultures can also be seen in the various answers that mention learning and actively participating in various Day of the Dead events. Such responses tend to indicate that our students recognize the importance of a multicultural society and enjoy learning about other cultures on both a local and global scale.

Some of the respondents’ statements indicate that their primary motivation for learning a new language is the desire to communicate with their local communities. For example, one participant looked forward to “getting to use it in the real world. In my hometown, there is a little Hispanic grocery store, and the owner and I have some pretty neat conversations in Spanish.” Consistently with the importance that language teachers give to the practicality that students see in L2 learning and the importance they give to L2 communication, various answers reflect that students enjoy learning “real conversational skills'' and “knowing how to better communicate with it both foreign and domestically.”

In recent decades, many language professors have made the case that a growing number of students are interested in learning languages for specific purposes. This phenomenon led to the creation of many courses of Spanish for the professions (e.g., Spanish for Business, Spanish for Healthcare) around the country (Doyle, 2019). This trend is also supported by research that highlights the traction gained by these types of language courses (Lafford et al., 2014) and the need for additional training and research around this topic (Hardin, 2015). Accordingly, Doyle (2018) stated that “Spanish for the Professions and Specific Purposes (SPSP) should flourish in the future as a paradigmatic curricular mainstay (p. 95).” However, the results of the study showed a notably different picture. Indeed, only four students expressed interest in learning Spanish as a way to improve their future professional careers. That being said, it is necessary to point out that our research did not focus on SPSP and that while many students may have a different primary motivation for learning a new language, they might also consider the benefits afforded to their future careers.

Finally, we consider the third group which includes students who were motivated to learn Spanish as a personal challenge. Some of them viewed learning an L2 as an educational goal or a way to prove to themselves that they can learn something new. As this student suggested, “the excitement for me came from having a new challenge that I was going to be able to try to master”, and this respondent also loved the idea of “being able to make sentences out of unrealistic ideas in the Spanish language”. As part of this category, we identified a group of heritage speakers of Spanish who may not feel confident in their grasp of the language. For them, studying Spanish is something of a very special nature, as it provides them with a potential means of connecting with their families and culture. These heritage speakers indicated that they were eager to communicate with relatives, e.g., “to talk to my aunt” or “being able to speak a language my grandparents speak,” to further develop their family relationships.

Topics of Interest of L2 Spanish Students

This section reviews the topics that our students reported as the most and least exciting. While these findings may not be surprising for language teachers, we believe they are useful for informing instructors about current students’ opinion on themes and topics. This proves to be helpful, as teachers may then capitalize on their students’ preferences to make classes more engaging and appealing. Before diving into these results, it is important to emphasize the role teachers play in selecting curricular content. Although students may dislike certain topics, some of these are actually necessary for developing language skills and are therefore non-negotiable components of a Spanish language course.

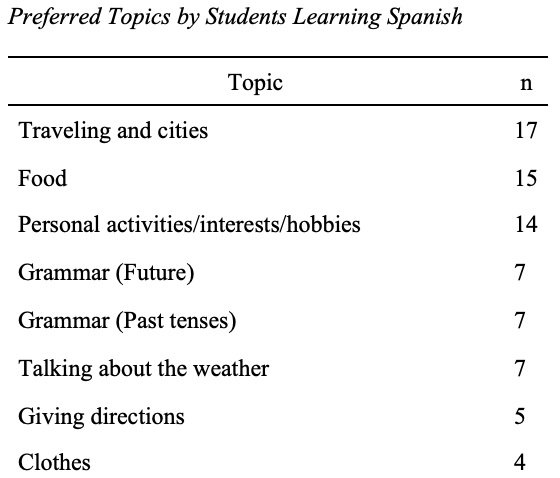

The previous section showed that students understand the importance of learning and practicing language components that allow them to easily communicate in the TL. Many of them also recognized the value of understanding different cultures and are eager to learn about them. Besides learning about communicating in the TL and its cultures, we identified several themes that seem to spark our students’ interest, as shown in Table 1, which includes the topics that were mentioned by more than 3 respondents. For the sake of simplicity, we focus here on traveling and food, as these were the most often mentioned topics.

Table 1

Preferred Topics by Students Learning Spanish

It should be noted that question 7 of the survey explicitly asked students to express their opinion about a series of topics to be included in an Elementary Spanish textbook and requested suggestions for additional topics. Most of the respondents expressed a favorable opinion about the proposed topics (food, family daily routine, free time, shopping, traveling, and sports). As indicated by some respondents, these topics seemed “like good important topics to cover” and “useful topics” worth keeping. Other respondents highlighted that while they “like these topics [they] would like to see more everyday discussions that [they] would encounter at [their] job that are super essential.”

The desire to learn “everyday phrases”, “speaking routines”, and “basic conversations” was a common answer. Additionally, various respondents restated that, besides these common topics, they would like to learn more about cultures of Spanish-speaking countries and that “ideally maybe there would be more Hispanic/Latinx cultured centered topics.”

Another expected result was learning which topic was viewed unfavorably by our students. To no one’s surprise, grammar is one of the least preferred topics for students learning Spanish. The usage difference between preterit and imperfect verbs gave “nightmares” to multiple students, while many confessed to “struggling” with all the different conjugations. However, many recognized that although “grammar isn’t fun to learn, [it] is necessary.” Another common theme that emerged (among our students) was their dislike to learning vocabulary or grammar topics that were deemed impractical for communication in the TL. For example, various respondents expressed frustration for having to learn about the pronoun “vosotros” [“You all” in Spanish]. They considered this “unnecessary,” since the overwhelming majority of Spanish speakers in the U.S. do not use this form. In the same vein, the respondents strongly opposed the idea of being taught vocabulary that was rarely used in everyday conversations, seemed outdated and had no apparent connection to the main topic of a lesson. For example, a respondent commented that “sometimes there will be a vocab word and I don't even know what that word means in English, so I just feel it doesn't help me.” Other respondents rightly pointed out that words related to technology (when not amended frequently) could quickly become outdated.

Inclusion of Social Justice Topics

To further understand the needs of the students, we asked them how they would feel if a language textbook explored more in-depth current themes and issues that seemed relevant to them. We classified the students' responses into three categories, based on whether they were in favor, indifferent, or against the inclusion of these topics. Furthermore, we identified three more categories. The actual number of respondents per theme are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Hierarchical Framework of All Tokens Regarding the Inclusion of Social Justice and Current Issues Topics.

A small portion (n = 39) of the students’ responses expressed opposition to the inclusion of these topics in the language classroom. Some of the students who were against it indicated that they believed it would not be helpful for their learning experience and would not provide pedagogical benefit, while others stated that they were against it for political reasons. For instance, this was evident in the following direct quotes: “If I wanted to learn politics, I’d take a politics class,” “I don’t think it is necessary…[to be] political when I just want to learn the language.” It is worth mentioning that some students did not like learning about social justice topics because they considered them above their level, e.g., “that may be for more advanced speakers, keep it simple for beginners. We don’t need to always be talking about world issues, it can be exhausting and not necessary for a beginning level Spanish course.”

On the other hand, the majority of the responses (n = 172) indicated a willingness to learn about social justice issues in the class. Accordingly, the students linked their interest to the feeling of being more engaged and connected to the world around them. Also, they stated a desire to learn about current themes and real-life scenarios instead of fictional situations. For example, a student commented: “I would love if the textbook handled contemporary issues or if it did not stray from talking about topics that do affect students’ lives. I use they/them pronouns but have opted to use “ella” [she] in Spanish as it aligns with my birth gender and usual gender expression in Spanish.”

In summary, it is important to provide a variety of topics/themes in the language classroom. The survey results suggest that current students would benefit from the inclusion of social justice topics to which they may relate. For instance, this was illustrated by the desire to use inclusive language so that all students would feel represented. In doing so, teachers should remain aware of the specific sensitivities as certain topics may be viewed as exhausting or anxiety-provoking, thus potentially leading to feelings of discomfort and a disengaged attitude. Overall, it is important to cultivate a relaxed environment that is conducive to learning and allows students to express themselves freely.

Teachers and Other Tools for Language Learning

Besides their motivations for learning a language and the types of topics they would like to see in a language classroom, many respondents had strong opinions about the homework learning platform, the textbooks used in their classes, and the ways they learn best.

Let us start with the negatives. Students were clearly unhappy with the current homework learning platforms used in our language classrooms, which many teachers relied upon heavily for a hybrid or flipped approach as they seemed disconnected to the textbook. According to the responses, “online learning is sometimes very difficult and the pages it refers to in the textbook are not very helpful,” and “it is hard to recall the homework without being able to access specifically what has been completed.” Although some students have strong feelings against these learning platforms, they still recognize their importance, and they “think something like that connected to a new textbook would be beneficial”. Other students asked us to find “a better platform out there for [them] to use.”

The negative comments regarding the current textbooks used in our classrooms, combined with a few additional responses highlighting the importance of the teachers, painted a clear picture of students’ learning needs. Not surprisingly, they “learn most while being engaged in the classroom” and recognized the important role played by a language teacher in helping them develop language communication skills. They also wish for a well-formatted textbook in which all information is easy to find. One respondent said, “The textbook has made it extremely difficult for me, someone with ADHD, to be able to use it due to how cluttered it is.” Students also would like to see more grammar explanations connected to the online homework. Finally, many students wished us luck with writing a textbook for Elementary Spanish learners, and they seemed engaged and happy to provide comments and suggestions for new learning resources.

Discussion

We sent out the student survey with the initial and rather narrow objective of gathering student feedback on potential topics to include in our OER Elementary Spanish textbook. We were pleased to receive so many responses and felt confident that they would guide our content selection process. What we did not expect to find was the overwhelmingly positive character linked to the set of motivations driving learning a required second language. Encouraging patterns emerged from the data which we found enlightening. Our students’ collective voices extolled the virtues of studying Spanish as a means of interfacing with other cultures and communities. Overall, we confirmed that our students are open-minded and accepting of others.

The survey responses further informed us about which themes should be given a top priority for our students. While we expected to find a standard list of topics such as food, clothing, and travel to be popular; we did not anticipate that a large number of respondents wished to see the inclusion of social justice issues and inclusive language in future iterations of their Spanish textbooks. We were also heartened to read comments that affirmed the crucial role of the instructor in helping engage students in the language learning process. Finally, the students who found fault with current homework learning platforms induced us to think critically about possible solutions or alternatives.

By analyzing our findings, we were able to develop many ideas about ways in which an OER textbook may address the needs of a diverse student population. One of the primary advantages of an OER text is its adaptability. Since these materials rely on electronic media and open-source content, they can easily be personalized based on the needs of a particular class or population. OERs’ adaptability also lets instructors modify a textbook to align more closely with their own needs or their institution’s L2 curriculum. This versatility allows teachers to feel confident that they provide a content that is both instructionally effective and supportive for their students.

To this end, we set to create a unique OER Spanish textbook based on the answers collected through a qualitative survey. Namely, we listened to the student voices that cited a desire for multicultural awareness and the ability to communicate with Spanish speakers in their hometowns. With this in mind, we designed a textbook featuring activities, information, and protagonists connected to the region where the majority of our students reside. Our expectation is that these personalized materials will resonate with our students and help them feel more motivated and engaged with the lessons.

As noted above, one of the student complaints about traditional textbooks is that the content quickly becomes outdated. For example, most of our students are well versed in technological trends and do not have any interest in learning out-of-date vocabulary. However, with traditional textbooks, students must wait years for a new edition, and given the fast rate of progress in technologies, it is very challenging to keep printed textbooks current. Adopting an OER textbook gives agency to instructors, not only by being able to update relevant information but also by having the capability of adapting and improving textbooks based on the students’ needs.

One of the most significant takeaways from our student survey and one that directly guided the way in which we address our students’ interests was the high number of responses that favored the inclusion of social justice topics. From our own experience in the classroom, we know that today’s students are educated about social issues and willing to talk about them. While we were already inclined to include current events in our Spanish textbook, the survey responses encouraged us to highlight social justice topics such as an immigration raid on a local meat packing plant and its devastating effect on the residents of a rural town in our region. Our students’ comments also reinforced our plan to feature inclusive language in our textbook. We chose to use the non-traditional feminine form as the base form in our vocabulary lists and presented the non-binary elle pronoun as part of our standard grammar. We made these decisions with our learners’ survey responses in mind and hoping that it will make them feel represented and valued.

In sum, OERs allow instructors to tailor their textbooks to include pertinent topics that directly impact their students. While most of our students favored learning about social justice topics in Spanish, we do acknowledge that this opinion was not unanimous. We thus encourage instructors to be cognizant that some students might be upset or anxious about discussing political topics in their language courses. OERs allow teachers to gauge their students when selecting material for their classes so that the classroom environment remains conducive to learning.

Limitations

The present study is not without limitations, and certainly the design of the survey to collect the data could be improved. First, the open-ended question, that required responses on the most common topics of Spanish textbooks, could have been presented free of examples in order to allow students to be more creative and spontaneous in their responses.

A second limitation is the lack of information about gender and gender identity in the demographic data which could have provided more information about the students’ preferences and wants. Among the background questions, we did not include one that inquired about the gender of the participant; adding this question could provide an extra layer of answers. We recommend further research about the students’ reasons to learning an L2, their topic preferences, and the inclusion of social justice topics—all within an OER framework; and also, we suggest the need for additional investigations on the type of themes developed in current OER language textbooks.

Conclusion

Many of our students’ responses showed a general sense of appreciation for our Spanish textbook project and wished us the best of luck. This demonstrates that our students felt engaged and happy to offer their suggestions for an improved textbook, even if it would only benefit future students. Certainly, textbooks are not dead. Rather, what is now defunct is a type of textbook unable to keep pace with our rapidly changing world. Our students have valuable input to offer about their L2 learning process, and they want to see their experiences and voices represented in the materials they use. OER textbooks are the next generation, and their ability to evolve and adapt may eventually render traditional textbooks obsolete.

References

Bali, M., Cronin, C., & Jhangiani, R. S. (2020). Framing Open Educational Practices from a Social Justice Perspective.

Journal of Interactive Media in Education, 2020(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.5334/jime.565

Bernaus, M. (2010). Language Classroom Motivation. In R. Gardner (Ed.). Motivation and Second Language Acquisition:

The Socio-Educational Model (1st edition, 181- 199). New York: Peter Lang.

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage.

Clinton, V., & Khan, S. (2019). Efficacy of open textbook adoption on learning performance and course withdrawal rates:

A meta-analysis. AERA Open, 5(3), 233285841987221. https://doi.org/10.1177/2332858419872212

Colvard, N. B., Watson, E. C., & Park, H. (2018). The Impact of Open Educational Resources on Various Student Success Metrics. International

Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 30(2), 262–272. Retrieved from: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1184998

Cuadrado, C., Melero, P., & Sacristán, E. (2018). Protagonistas. Vista Higher Learning.

Dörnyei, Z. (2009). The L2 Motivational Self System. In Z. Dörnyei & E. Ushioda (Eds.), Motivation, Language Identity and the L2 Self (pp. 9-42).

Multilingual Matters.

Doyle, M. S. (2018). Spanish for the professions and specific purposes: Curricular mainstay. Hispania, 100(5), 95–101.

https://doi.org/10.1353/hpn.2018.0023

Doyle, M. S. (2019). Curriculum development activism (CDA): Moving forward with Spanish for the professions and specific purposes (SPSP).

Hispania, 102(4), 475–480. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpn.2019.0130

Foucault, M. (1982). The subject and power. Critical Inquiry, 8(4), 777–795. https://doi.org/10.1086/448181

Gardner, R. (2010). Motivation and Second Language Acquisition: The Socio-Educational Model (1st ed.). Peter Lang.

Hardin, K. (2015). An overview of medical Spanish curricula in the United States. Hispania, 98(4), 640–661. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpn.2015.0118

Hilliard, A. D. (2014). A critical examination of representation and culture in four English language textbooks.

Language Education in Asia, 5(2), 238-252.

Hilton, J., III. (2016). Open educational resources and college textbook choices: A review of research on efficacy and perceptions. Educational

Technology Research and Development, 64(4), 573–590. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-016-9434-9

Hilton, J., III. (2019). Open educational resources, student efficacy, and user perceptions: A synthesis of research published between 2015 and

2018. Educational Technology Research and Development, 68(3), 853–876. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-019-09700-4

Jenkins, J., Sánchez, L., Schraedley, M., Hannans, J., Navick, N. & Young, J. (2020). Textbook Broke: Textbook Affordability as a Social Justice Issue.

Journal of Interactive Media in Education, 2020(1): 3, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.5334/jime.549

Korell, J. L. (2021). A corpus-based study of gender representation in ELE textbooks—Language, illustrations and topic areas.

Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 12(2), 211-221.

Lafford, B. A., Abbott, A., & Lear, D. (2014). Spanish in the professions and in the community in the US. Journal of Spanish Language Teaching,

1(2), 171–186. https://doi.org/10.1080/23247797.2014.970361

McKay, S. (2003). Teaching English as an international language: The Chilean context. ELT Journal, 57(2), 139-148.

Morris-Babb, M., & Henderson, S. (2012). An experiment in open-access textbook publishing: Changing the world one textbook at a time.

Journal of Scholarly Publishing, 43(2), 148–155. https://doi.org/10.3138/jsp.43.2.148

Robles, G. (2007). Where are women in Spanish second language textbooks? What do they do? Who are they? In J. Santaemilia, P. Bou & S.

Maruenda (Eds.), International perspectives on language and gender (8th ed., pp. 553-569). Universitat de València.

Seiferle-Valencia, M. (2020). It’s Not (Just) About the Cost: Academic Libraries and Intentionally Engaged OER for Social Justice.

ibrary Trends, 69(2), 469-487. https://doi.org/10.1353/lib.2020.0042

Siegel, A. (2014). What should we talk about? The authenticity of textbook topics. ELT Journal, 68(4), 363–375. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccu012

Appendix A

A selection of recently published Spanish OER textbooks.

Appendix B

Survey questions

Consent agreement.

What is your age?

Are you a minority student?

What is your background?

Are you a first-generation student (meaning a student whose parents did not complete a four-year degree)?

Based on your current and past experience, do you remember the topic that most excited you while taking a language course?

Is there a topic you really hated, and you hope to never find again in a language textbook?

What types of topics should be included in your ideal Elementary Spanish Textbook? Many textbooks cover the following thematic topics: la comida, la familia, la rutina diaria, el tiempo libre, las compras, los viajes, los deportes. Do you like these topics, or would you like to see other topics covered by our textbook?

How would you feel if your language textbook included more in depth/relevant (to you) topics that explore current themes, issues, etc.?

Use this space to leave any additional comments for us as we plan our textbook.