Measuring Study-Abroad Students’ Intercultural Communicative Competence in Japanese

Measuring Study-Abroad Students’ Intercultural Communicative Competence in Japanese

Hiromi Tobaru

Department of Modern Languages and Literatures, California State University, Fullerton

Abstract

This study examined the Japanese speech style-shifting of seven participants before and after a year of study abroad (SA) in Japan to evaluate intercultural communicative competence (ICC) development. The mixed-method analysis revealed that participants shifted their speech style more actively in the post-SA interviews than in the pre-SA interviews. Qualitative analysis also indicated that the participants’ speech style-shifting in the post-SA interviews helped them sound more approachable while maintaining the appropriate level of formality and politeness, which suggests development in ICC. Based on the findings, this article also discusses pedagogical implications and future research suggestions for ICC in SA contexts. (98)

Keywords: intercultural communicative competence; Japanese speech style shifting; assessment of study abroad learning

Introduction

As globalization continues to expand, intercultural competence has become a central goal for many higher education institutions in the United States, and study-abroad programs have been widely recognized as a valuable tool for fostering students’ intercultural competence (Taguchi & Collentine, 2018). However, there is ongoing discussion about how to define and measure intercultural competence and its components (Deardorff & Jones, 2012).

The definition of intercultural competences varies among scholars as well as in the academic fields (Deardorff & Jones, 2012). In foreign language education and applied linguistics, the term intercultural communicative competence, in relation to communicative competence, is increasingly used instead of intercultural competence (Barili & Byram, 2021; Fantini, 2018). Intercultural communicative competence refers to the ability to effectively communicate and interact with individuals from different cultural backgrounds. This includes the understanding of cultural differences, sensitivity to cultural norms and values, and the skill to adapt communication strategies appropriately in intercultural contexts (Byram, 1997; Byram & Wagner, 2018). Because this paper focus on measuring foreign language learners’ communication skills, I will use Intercultural communicative competence (ICC) instead of intercultural competence (IC).

The linguistic and sociolinguistic components crucial for foreign language (FL) learners to communicate effectively and appropriately may vary depending on their native language (L1) and culture (C1) and the target language (TL) and culture (TC). Previous research on American SA learners in Japan suggests that the ability to shift speech style effectively and appropriately is a crucial for building close relationships with locals (Iwasaki, 2011; Tobaru, 2019), thereby, considered as one of essential components of ICC for SA students in Japan.

In the Japanese language, there are two main speech styles: plain forms and desu/masu forms (hereafter masu form). Plain forms often predominate in casual conversation between persons whose relationship is personal and intimate, in settings that do not demand formality. Masu forms, on the other hand, identify the speaker as showing “solicitude toward, and maintaining some linguistic distance from the addressee” (Jorden & Noda 1987, p. 32) especially in a spoken communication. Unlike English, Japanese has no socially neutral predicate form for ending a full sentence, and a Japanese speaker must choose between plain form and masu form depending on the context. For example, the English sentence, Mr. Tanaka eats a cake can be expressed in both masu-form ending and plain form ending.

Tanaka-san ga keeki o tabe-masu. [Mr. Tanaka eats a cake.]

Mr. Tanaka, SUB, cake, OB, eat (masu form).

Tanaka-san ga keeki o taberu. [Mr. Tanaka eats a cake.]

Mr. Tanaka, SUB, cake, OB, eat (plain form).

Note that both sentences are equivalent in structure—placement of the subject (Mr. Tanaka), object (cake), and verb—and differ only in the form of verb. Although the English equivalents for both plain and masu forms are the same, the social stances indexed with those two forms differ. Therefore, the differences in the social stances indexed with the two examples above can be considered differences in the stances that the speaker takes vis-à-vis their addressee. For example, in the same setting, Tanaka-san ga keeki o taberu may be uttered to someone with whom the speaker feels intimate, such as a friend or a family member, whereas Tanaka-san ga keeki o tabemasu may be said to someone with whom the speaker feels less intimate and to whom they may feel the need to indicate respect or social distance, such as a superior or a business partner.

As globalization has advanced, scholars of second/foreign language education have shifted their focus from developing native-like language proficiency to developing skills that enable speakers to communicate successfully with people from different linguistic and cultural backgrounds (Tran & Duong, 2018 Kramsch, 2009; Walker, 2010; Moody, 2018; Zhang & Jian, 2021, etc.). In addition, with the advancement of technology and the popularity of generative artificial intelligence (AI), the development of skills in oral communication and in-person communication may gain more importance in the coming years, especially in foreign language education. The content produced by generative AI can be well organized but is often overly neutral and impersonal, which may be preferred in formal writing for academic and business settings but is inadequate for building a personal relationship in in-person settings. This phenomenon requires rethinking what skills are needed for FL learners to be successful in the modern society.

My attempt of this paper is to demonstrate that examination of Japanese speech style shifting is an effective way to measure ICC of foreign language learners, which reflects linguistic and cultural skills relevant to the current society. To do so, this study examines American FL learners’ speech style shifting in an intercultural communication context. Specifically, this study analyzes seven study abroad (SA) students’ Japanese speech style shifting before and after an academic year of SA in Japan.

Literature Review

This section first reviews research on ICC and its measurements in various contexts including study abroad contexts. It then reviews speech style in Japanese and discusses why examination of Japanese speech style shifting is a suitable measurement for SA students’ ICC development in Japan.

Intercultural Communicative Competence and Measurements in SA Contexts

ICC has been studied by scholars in various fields. Although these scholars have not agreed on one definition and components of ICC, three components are common to these definitions, which includes the cognitive, affective, and behavioral aspects (Bennett, 2009; Chen & Starosta, 1997; Deardorff, 2006; Perry & Southwell, 2011). The cognitive aspect involves students’ comprehension of the target culture and their recognition of differences between their own culture and others (Hill, 2006). Affective sensitivity, as defined by Chen and Starosta (1998), encompasses an individual’s active desire to understand, appreciate, and accept cultural differences, including elements such as participation in communication, confidence in intercultural interactions, acknowledgment and respect for cultural disparities, enjoyment in communication, and attentiveness in communicative situations. Koester and Olebe (1988) describe the behavioral dimension as comprising respect, interaction management, and tolerance of ambiguity, while Kelley and Meyers (1995) suggest it includes cross-cultural adaptability. Despite the behavioral dimension may be the most relevant to ICC in foreign language education (Portalla & Chen, 2010; Lee & Song, 2019; Fantini, 2018), it is less researched than its cognitive and affective counterparts and remains somewhat ambiguous (Lee & Song, 2019).

In the field of foreign language education, Michaele Byram (1997; 2008; 2018) developed a theoretical framework of intercultural communicative competence focusing more and communication skills, such as “knowing how to interactive people with different ways of thinking, believing and behaving” (Byram, 209, p. 321). ICC was also made some connection with an established concept of communicative competence (Hymes,1964), which had been applied in second/foreign language education in 1990s (Byram, 2012). Communicative competence (CC) refers to the ability to use grammatical competence to communicate appropriately in a variety of contexts, which often refers to a native (L1) speaker’s communicative competence in their native language. Byram (2012) points out that “aiming for CC in foreign language education is misleading because it implicitly suggests that foreign language learners should model themselves on first language speakers, ignoring the significance of social identities and cultural competence of the learners” (p. 8).

According to Byram, a competent intercultural speaker possesses, Savoir (i.e., knowledge of self and other, of interaction); Savoir être (i.e., relativizing self, valuing other), including tendency to “actively seek[s] the other’s perspectives and evaluation of phenomenon”; Savoir comprendre (skills of interpreting and relating), such as being able to identify causes of misunderstanding … and dysfunctions; Savoir apprendre/faire (skills of discovering and/or interacting), such as being able to “use a range of questioning techniques”; and Savoir s’engager (political education, critical cultural awareness) (adapted from Byram 2008, p230).

He suggests that the capacities for learning and doing (savoir apprendre/faire) encompass the skills needed to gain fresh insights into a culture and its practices, and the proficiency to apply knowledge, attitudes, and skills effectively in live communication and interaction scenarios (p. 52). Attitudes (savoir être) involve qualities like curiosity and receptiveness, alongside a willingness to temporarily set aside preconceptions about other cultures and one’s own beliefs (p. 50).

Previous SA studies on ICC have tended to focus on measuring students’ knowledge and attitude through questionnaires (van Berg et al., 2009; Simemoe et al., 2014) or other studies have treated ICC as learners’ psychological changes, such as self-identity and individual differences (Munezane, 2019). It is important to investigate the behavioral aspect of ICC that reflect SA students’ skills “to effectively use the target language in bridging cultural differences” (Tran & Duong, 2018, p. 389) and to “collaboratively shape interactions and relationships” that are mutually beneficial (Jian, 2021).

Studies on English-speaking SA students in Japan have reported that SA students often struggle with the different speech styles in Japanese, which resulted in difficulty in building relationships with locals (Burns, 1996; Iwasaki, 2011; Siegal, 1995; Taguchi, 2015; Tobaru, 2019). Because there is no “neutral speech style”, a speaker of Japanese consistently needs to choose an appropriate speech style ending to reflect not only their relationships with the addressee, but also their stance and attitude toward the topic. As it will be discussed in the following section, this skill is crucial to communicative appropriately and effectively, thereby, building a strong relationship with Japanese speakers. This makes examination of SA students’ style shifting development is an ideal measurement the behavioral dimension of ICC by SA students in Japan.

Style Shifting by Japanese L1 Speakers

As mentioned above, a speaker of Japanese must choose either a plain form or a masu form at an utterance ending, since other than incomplete sentences, there is no neutral speech style in the language. Although plain forms are often associated with informal/casual communicative activity and masu forms with polite social intercourse, research suggests that Japanese L1 speakers use both forms within a single conversation, with the choice of form depending on various contextual factors, including gender, age, social status, and relationship of the speakers, as well as the place, time, and purpose of the conversation.

Ikuta (1983) proposed that masu and plain forms signify degrees of social, attitudinal, or cohesion distance rather than politeness or formality. Speakers choose speech styles at the start of conversations based on social distance, with their attitudinal distance shifting throughout the interaction. Maynard (1993) emphasized the importance of addressee awareness in speech style shifts within masu-form contexts. Speakers use masu forms when they see the addressee as psychologically separate, often due to higher social status (high-awareness). Conversely, plain forms are used with close friends in casual settings, reflecting low addressee awareness and psychological closeness. Cook (2008b) classified plain forms into two styles based on their usage: informal speech style (IfSS) and detached speech style (DtSS). IfSS plain forms (IfSS-PF) are frequently employed with affect keys, such as a sentence-final particle, vowel lengthening, rising intonation, or certain voice qualities. DtSS plain forms (DtSS-PF) are generally in a naked plain form (NPF) indicating “devoid of emotion” (p. 85) and are used to provide “foregrounds and referential content of an utterance” (p. 85) without addressing any specific audience.

In addition to two different form endings, Japanese speakers often end their utterances with kedo [but] and node/kara [because] without completing a full sentence, which occurs most frequently in spoken communication. In this paper, such a sentence ending is referred as an incomplete sentence. An incomplete sentence is often used when a clause is part of an idiomatic expression that conveys the entire meaning even when shortened, or when it is linked by a (pseudo-)logical connector, making the intended message either contextually obvious or established by convention (Ohori, 1996). Speakers also use incomplete sentences as communication strategies, such as to avoid redundancy of previously stated information, to indicate the pragmatic effect of “that’s right, but that’s not the whole story” with a warning tone (Ohori, 1996), or to soften the utterance and hence to evoke the polite affect (Itani, 1992).

Japanese L1 speakers utilize plain form endings in masu-form predominant contexts for soliloquy-like expressions, such as exclamatory statements, sudden recollections, self-reflection, and self-affirmation, and for co-constructing ideas (Cook, 2006; Ikuta, 2008, Makino, 2002 Okamoto, 1999). Furthermore, style shifting is used to avoid sounding too friendly or too formal, but the extent of style shifting in a masu-form-predominant discourse context varies depending on the speakers (Okamoto, 1999).

Style Shifting Japanese FL Speakers

Considering the complexity of style shifting, it is no surprise that research on Japanese FL learners’ style shifting reveals that even advanced FL learners struggle to manage such skills (Cook, 2016; Masuda, 2010; Okazaki, 2015; Taguchi, 2015). Researchers who compared Japanese L1 and L2/FL speakers’ speech style shifting in a masu-form-predominant context have reported that Japanese L2/FL speakers tended to use more masu-form endings than Japanese L1 speakers (Masuda, 2010; Okazaki, 2015). Masuda (2010) reported that Japanese L1 students used incomplete sentences, (i.e., “others” in Masuda’s study) far more frequently than the Japanese L2 speakers when they were talking about themselves or engaging in joint utterances. However, Japanese L1 students used masu forms mostly in high-addressee-awareness situations, such as when directly asking or answering a professor’s questions, when expressing acknowledgment and agreement, or when communicating an assessment or a confirmation. Masuda also reported that FL participants with study-abroad experiences used more plain forms than those without study abroad experience.

Okazaki (2015) reported that 14.4% of the plain forms used by the advanced L2 speakers were categorized as informal speech style, compared to only 2.2% for L1 speakers. Okazaki further reported that L2 speakers often inappropriately used sentence-final particles (e.g., ne, yo, or yo ne), rising intonation, and question words (such as nani or nan te/to iu) for their soliloquy expressions, thereby projecting an informal speech style rather than the intended soliloquy expressions. (summarize this section).

In terms of speech style development in SA students, Kasper and Rose (2002) argued that “students learn a more informal style during study abroad than at home in the classroom” (p. 230). Similar tendencies have reported by researchers who examined on Japanese style-shifting development in SA contexts by comparing pre- and post-SA results. SA students tend to decrease use of masu-form sentence endings upon their return from Japan, and many of them overused plain-form sentence endings (Marriot, 1995, Taguchi, 2015, Iwasaki, 2008).

Taguchi (2015) further reported that the most used affect keys with plain forms were rising intonation. In the beginning of SA, participants used plain forms with rising intonation to check their conversation partners’ comprehension of what they said, which suggests “learners limited linguistic competence and greater reliance of communicative strategies” (Taguchi, 2015, p. 69). On the other hand, in the post-tests, the participants used more plain forms with rising intonation in a normal function of asking questions.

Cook (2016), who examined two SA participants’ style shifting change, also reported one of her participants, whose pre-SA proficiency was intermediate-low, used plain forms mostly for next-turn-repair-initiators (NTRIs), such as repeating with rising intonation when an unknown expression mentioned by her host family, and for assessments, such as “muzukashii” [it’s difficult (to explain)]. On the other hand, the other participant, whose pre-SA proficiency was intermediate-mid level, actively participated in dinnertime conversation with her host family, used plain forms, such as zenzen wakaranakatta [I didn’t understand the content] to express affective intensity, and articulated detached stance markers when narrating her story. Iwasaki (2008) also reported that two of her participants, whose oral proficiency before and after SA were relatively lower than the other participants, overused plain forms upon their return although they used masu form predominantly before SA. Interestingly, these two participants still used masu forms in contexts in which “expressing deference is highly needed” (Iwasaki, 2008, p. 62), concluding that these learners had “some understanding of the social meaning of the two speech styles” (p. 68). Cook and Iwasaki’s studies suggest that SA students’ language proficiency may play some roles in FL learners’ speech style shifting ability in Japanese.

Researchers exploring the development of Japanese speech style shifting among FL learners often refer to the skill of appropriately shifting speech styles as “pragmatic competence” (Cook, 2016; Iwasaki, 2008; Taguchi, 2015). Pragmatic competence is defined as “the ability to convey and interpret meaning appropriately in social situations” (Taguchi, 2009), but this concept is rooted in how native (L1) speakers use the language in communication (i.e., CC). However, as some researchers have pointed out, L1 speakers do not necessarily anticipate that FL learners will acquire the same norms of their language in the current global society (Jian, 2021; Zeng, 2021; Moody, 2018). Solely focusing on pragmatic competence based on L1 speakers’ norms might not be synonymous with achieving ICC for communication in the language (Byram, 2012).

Furthermore, we need to examine how SA students’ speech style-shifting would be evaluated by Japanese speakers with whom they interact because the “appropriateness” of the behavior “can be determined only by the other person” (Fantini, 2009, p. 287). A measurement of ICC should focus on strategic use of speech styles that are still considered acceptable, although they may be derived from L1 speakers’ norms. Furthermore, studies that consider the behavioral aspect of ICC development are still limited, especially for FL learners of less commonly taught languages, such as Japanese. The current study aims to fill these gaps by examining seven students’ Japanese style-shift development before and after one-year period of study abroad.

Method

Participants

The current study involved undergraduate students from a large public research university in the United States. Eight students originally agreed to participate in the current study after receiving detailed explanations of the study procedure, but one participant was removed due to a lack of submitted data. All participants were white, U.S. born and raised, and spoke English as their native language and used it as a primary language for daily communication. Table 1 presents the seven participants (with pseudonyms), their Japanese language course completion at the home institution, their previous experience in Japan, and unofficial oral proficiency interview (OPI) ratings before and after SA sojourns. Japanese language students (levels 1 to 3) at the home institution attended five 50-minute sessions a week.

Table 1

Background information of the participants

[1] NH = Novice High; IL = Intermediate Low; IM = Intermediate Mid; AL = Advanced-low

[1] Please see the Appendix for a list of sentence-structure abbreviations used in the translated in interview excerpts.

Instruments: Japanese Interviews

The current study employed Japanese interviews to collect data on SA students’ style-shifting development. The Japanese interviews followed the format of the American Council on Teaching of Foreign Languages (ACTFL) OPI test, which enabled me to measure the participants’ language-proficiency gain and to compare the current findings with previous studies. The OPI test is a one-on-one interview in a target language that is designed to measure speaking skills. An interviewer elicits various speaking tasks, ranging from answering a simple direct question (e.g., “What is your hobby?”) to engaging in complicated tasks such as stating and defending opinions on social issues and discussing hypothetical situations. The ACTFL OPI rates proficiency according to five major levels: Novice, Intermediate, Advanced, Superior, and Distinguished. Speakers at the Novice-high to Intermediate-low levels, can create their own sentences rather than producing merely recalled expressions, but their speech may still exemplify difficulties in communicating. Speakers at the Intermediate levels have no difficulties talking about topics related to themselves but may show some difficulties discussing topics beyond their own interests. Speakers at the Advanced levels can discuss complicated issues by expressing and supporting their opinions (ACTFL, 2012). One of the downsides is that because of the breadth of the OPI proficiency levels, a student can have acquired greater proficiency post-SA yet remain rated at their pre-SA level (Baker-Smemoe et al., 2014). Prior to conducting the interviews, I twice completed a four-day OPI workshop hosted by ACTFL, conducted the Japanese interviews.

To elicit certain abilities not easily obtained in the conversational format of OPI (ACTFL, 2012), test takers, whose proficiency level ranged from Novice-high to Superior, participated in role-playing. However, the appropriate speech style for the role-play tasks varied by participant; therefore, I excluded the data of the role-play contexts for the data analyses.

Procedure and Data Analysis

All audio recordings of OPI tests were transcribed for quantitative and qualitative analyses. In the quantitative analysis, the participants’ final-utterance forms were counted and examined. All utterance-final forms were categorized into masu forms, including hai (a formal ‘yes’); plain forms, including “un,” an informal counterpart of “hai”, and incomplete sentences. In the current study, incomplete sentences include suspended clauses, particle ending utterances, and others (ending with expressions like, chotto, daitai, etc.). Utterance endings that exemplified linguistic difficulty, such as switching to English, or using an incomplete sentence before an utterance like, “setsumei dekimasen” [I cannot explain it (in Japanese)] were excluded from the analysis.

For the qualitative analysis, all plain forms were categorized into informal speech style plain forms (hereafter IfSS-PFs) or detached speech style plain forms (hereafter DtSS-PFs). IfSS-PFs are often produced with affect keys and indicate an intimacy to the interlocutor by indexing the speaker’s off-stage, relaxed, and uninhibited stance. On the other hand, DtSS-plain forms are “devoid of emotion” and do not indicate intimacy toward the interlocutor. They are often produced without any affective keys (Cook, 2008b). However, some DtSS-PFs, especially for soliloquy-like utterances, are not limited to NPFs, but also include plain forms with affect keys, for example, the multiple sentence-final particles ka na [I wonder] in the phrase kinoo datta ka na [I wonder if it was yesterday]. Therefore, in the current study, DtSS-PFs refer to plain forms that signal low-addressee awareness (Maynard, 1993, p. 178). Furthermore, plain forms that are used to co-construct ideas or provide background information are also categorized as DtSS-PFs in the current study. When a speaker uses DtSS-PFs, they tend to focus on the contents of the statement rather than the relationship with the conversation partner. Strategic use of DtSS-PFs can facilitate the conversation without violating the relationship, which is one of the crucial aspects of ICC. Following the previous studies’ findings discussed above, DtSS-PFs in this study are ascribed four primary functions: soliloquy-like utterances (which include recalling something and self-reflections), exclamatory expressions, expressing affective intensity when narrating a story, and co-constructions with an interlocutor.

Findings

Findings from Quantitative Analysis

This section presents findings from the quantitative analysis. Chart 1 shows the total number of occurrences by category. It includes masu-form endings, plain-form endings, and incomplete sentences (IncS).

Although three participants—Bobby, Emma, and Isabelle— showed a decrease in the number of utterances post-SA, they did not necessarily speak less. In fact, Isabelle and Emma tended to produce longer and more complex clauses in the post-SA interviews than in the pre-SA interviews.

All participants used masu forms predominantly both before and after SA programs in Japan. However, the degree of change was dramatically different among the participants. The reduction of the masu form was especially remarkable for Emma, Henry, and Isabelle, all of whom decreased their use of masu forms by more than 20% in the post-SA interviews. In terms of the use of incomplete sentences (“IncS” in the chart), all of them increased the use in the post-SA interviews.

Changes in Functions of Plain Form Use

Chart 2 shows different functions of plain forms used in pre- and post-SA interviews. Among the different functions of plain forms, next-turn-repair initiatives (NTRI) and assessments are unique to non-native speakers of Japanese and can be considered as direct results of a speaker’s lack of Japanese language proficiency (Cook, 2016; Taguchi, 2015; Okazaki, 2015). Overall, the use of these two types of plain forms decreased in post-SA interviews, with the degree of decrease varying across individual study participants. However, Emma and Frank increased the use of these two types of plain forms, which I discuss in more details in the section of the qualitative findings.

Increase Use and Changes in Incomplete Sentences

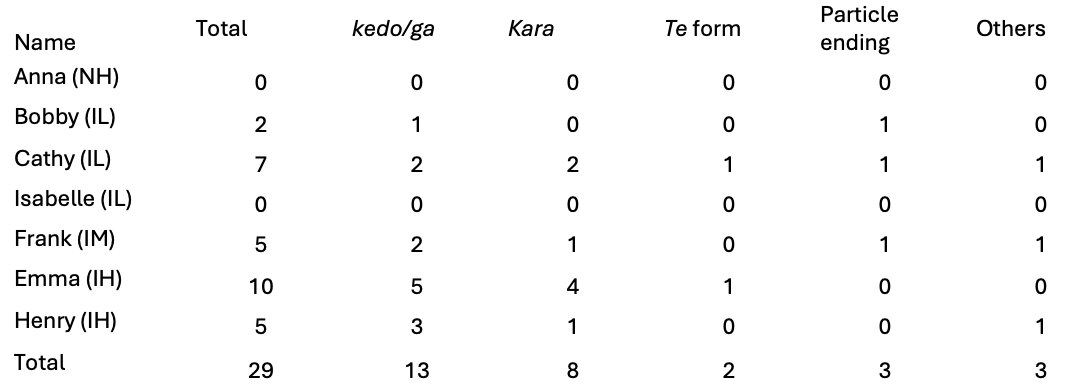

Tables 1 and 2 below further categorize the participants’ incomplete-sentence use in pre- and post-SA interviews into different endings; Table 1 (pre-SA) shows the endings kedo/ga, kara, te-form, and particle endings; Table 2 (post-SA) adds tari, toka, and mitai. The category “others” comprises utterance-ending extent expressions, tototemo, chotto, daitai, amari, and tsuite.

Table 1

Pre-SA Japanese Interviews

Table 2

Post-SA Japanese Interviews

Prior to SA, only five participants used incomplete sentences in their speech. However, upon their return, all of them used incomplete sentences in their utterances. They also used more varieties of utterance endings. Before SA, 80.8% of 26 suspended clauses were kara [because] and kedo [but] clauses, but upon their returns, the total number was more than triple, and kara/kedo clauses only accounted for 44.7%. Cathy, Isabelle, Frank, Emma, and Henry began using -tari, -toka, and -mitai as their utterance final forms. The most remarkable increase of incomplete sentences was evidenced by Henry, who rated Advanced-low upon his return and who used incomplete sentences more than three times more frequently, with a variety of endings than he had in the pre-SA interviews.

Findings From the Qualitative Analysis

Decrease of Inappropriate Use of Informal-Speech-Style Plain Forms (IfSS-PFs)

The qualitative analysis revealed that Anna, Bobby, Cathy, and Isabelle used inappropriate IfSS-PFs in a context categorized as high-awareness-addressee situations during the pre-SA interviews. Use of IfSS-PFs for speech acts, such as in requests, apologies, and expressions of thanks in masu-predominant contexts, is often considered rude and disrespectful (Iwasaki, 2008). Excerpt 1 below shows that Bobby inappropriately omitted gozaimasu for the speech act of thanking. When the interviewer indicated the end of the interview by saying “Arigatoo gozaimashita” [thank you] to indicate the end of the interview (line 1), Bobby responded with the inappropriate plain-form equivalent, arigatoo (line 2)[1].

Excerpt 1 (Bobby, Pre-SA)

However, in the post-SA interview, Bobby was able to perform the same speech act in a culturally appropriate manner as shown in Excerpt 2. This time, the interviewer used a different phrasing to close the interview, otsukaresama desu [You must be tired] (line 1), which is also often used at the end of a meeting or a class. Bobby responded to the greeting slightly differently by conjugating the copula ending (desu), which is also acceptable in the context and shows that he was not merely parroting the interviewer’s speech.

Excerpt 2 (Bobby, Post-SA Japanese Interview)

Likewise, Isabelle and Cathy used IfSS-PFs and the te-form request inappropriately when they requested that the interviewer repeat what she said.

Excerpt 4 (Isabelle, Pre-SA Japanese interview)

In line 2, Isabelle asks the interviewer to wait for a second by using a verb te-form, matte, which is an informal request form. She then provides the reason for her request in a plain form “kikoenikukatta” [it was difficult to hear] in line 3. Similarly, Cathy asked the interviewer to repeat by using omission of copula, “maffin-chan (the name of her pet) wa ookii kara, moo ichido” [one more time because my pet was too loud (and I couldn’t hear what you said)]. Therefore, Isabelle’s use of IfSS-PFs and Cathy’s use of incomplete sentence for making requests were considered inappropriate in the contexts.

In the post-SA interview, however, Isabelle demonstrated not only her enhanced cultural knowledge in recognizing her inappropriate speech style but also her linguistic knowledge in correcting herself naturally. Excerpt 4 shows Isabelle’s development of such intercultural communicative competence. Prior to this excerpt, Isabelle had been describing a movie she had recently watched, and she mentioned that the heroine wanted to do things that high schoolers would do (“Kokosei mitai na koto wo shitai to omotte ita kara” [because (the heroine) wanted to things like high school students would do]). The interviewer asked her to elaborate on what she meant by “kokosei mitai na koto” (line 1).

Excerpt 5 (Isabelle, Post-SA Interview)

In line 2, Isabelle was describing what she meant by “koukou-sei mitai na koto” [things that high school students are likely to do], but in line 3, she also stated that it was difficult to understand what American eighth-graders normally do (or are allowed to do) if a person is non-American. In line 4, she expressed the difficulty by using a plain form, muzukashii [it is difficult], with multiple SFPs, yo ne, which may add an “obtrusive” tone; many Japanese L1 speakers avoid using these when speaking with someone of higher social status (Izuhara, 2003). However, in line 5, she immediately corrected herself by adding a more detailed explanation of why it was difficult to understand with the masu form (omoimasu [I think]), which canceled out her inappropriate use of yo ne in the previous utterance.

Changes In DtSS-PFs And IfSS-PFs

Prior to their SA sojourns, most participants used DtSS-PFs without sentence-final particles (SFP) for soliloquy to digest the word by repeating after the interviewer or for their own self-conviction (Makino, 2002; Ikuta, 2008). Only Emma used DtSS-PF with the recalling SPF kke (i.e., nan da kke [what was it]) in the pre-SA interviews.

In the post-SA interviews, Cathy and Frank used DtSS-PFs with SFP more actively. For example, Cathy used multiple SFPs ka na (e.g., kinoo datta ka na [I wonder it was yesterday]) to describe her attitude toward the interviewer. Below are some examples of Cathy’s DtSS-PFs use in the post-SA interviews.

Excerpt 5 (Cathy, Post-SA Japanese interview)

Cathy described that she worried about crimes in her city in line 1, where she used a masu form ending. When the interviewer asked Cathy to provide more information about the crimes, Cathy began by describing one incident (line 3) by using the plain form kinoo datta [it was yesterday], with multiple SPFs ka na [I wonder]. When SPFs ka na is followed by a plain form, the resultant meaning is one of wondering or supposing, and it makes an utterance sound like a soliloquy rather than something directed toward the addressee (Cook, 2006; Masuda, 2010; Okazaki, 2015). Therefore, Cathy’s plain-form use with the SPF ka na in line 3 is appropriate. Immediately after the soliloquy utterance, Cathy continued describing the crime in masu form, which suggests her ICC development. Similar DtSS-PF use was observed in Frank’s post-SA Japanese, “hon-dana da kke” [I’m trying to recall if it was called hon-dana] when he was trying to figure out if the word hon-dana was the right word.

However, not all changes are considered indicators of ICC development. For example, Frank also used “nan to iu” [what is it called (how do I say it)?] when he was trying to remember some information. The same use of “nan to iu” which is considered an IfSS interrogative in Japanese, was also observed several times in Emma’s post-SA Japanese. As previously stated, Emma used the DtSS-PF nan da kke [I’m trying to recall what it was] three times in the pre-SA OPI when she was trying to recall information. However, after returning from Japan, she no longer used nan da kke [I’m trying to recall what it was] but used nan to/te iu [what is it called?].

Use of NTRI: Inappropriate Use of IfSS-PF

As noted previously, use of next-turn-repair initiative (NTRI) is particular to L2 Japanese speakers, and it is indicative of a learner’s limited linguistic competence (Taguchi, 2015). Excerpt 6 shows an example of NTRI use by Anna, but all participants, except Isabelle and Henry, used NTRI prior to their SA sojourns.

Excerpt 6 (Anna, Post-SA Japanese Interview)

Upon return from SA, Cathy no longer used NTRI and began using SFP (datta) ka na as discussed in Excerpt 5. However, the other participants’ utterances, except for Henry’s, still included NTRI uses, but most of them used NTRI less frequently than they had pre-SA.

DtSS-PF for Co-constructions

All participants also used plain forms when the interviewer asked follow-up questions or when asking questions to seek help recalling a word or phrase that the participant had previously mentioned. Such use of plain forms is categorized as detached plain forms because L1 speakers use them when they focus on the content of the information rather than on the relationships with their conversation partners. Excerpt 7 shows an example from Henry’s post-SA interview.

In line 1, the interviewer asked why Matsushima was his favorite. From line 2 to line 9, where Henry responded to the interviewer’s questions, Henry used masu forms appropriately with multiple clauses (lines 4-9). In line 10, the interviewer forgot the name of the place, so she asked the information with the recalling SFP kke. To the recalling question, Henry responded with a noun without a copula (NPw/oC) in line 11. Henry’s use of NPw/oC in line 11 is similar to what Ikuta (2008) considered a backchannel “to facilitate the completion” (p. 81) of the interviewer’s preceding utterance, “Kondo itte mimasu” [I try to go (there)] in line 12. After the interviewer expressed her interest in going there, Henry shifted his speech style to the masu-form equivalent of a request form “please” (i.e., -te kudasai), which reflects Henry’ high-awareness of the addressee.

Discussion

The quantitative analysis revealed two key findings: that for all participant, use of masu forms decreased in the post-SA interviews (85.5% to 72.1%), and use of incomplete sentences increased. Without the data from the qualitative analysis, the findings might suggest that “students learn a more informal style during study abroad than at home in the classroom” (Kasper and Rose, 2002, p. 230). However, the findings from the qualitative analysis suggest that students learned appropriate use of plain forms during study abroad and used it more strategically so that they could sound more approachable while maintaining the appropriate level of politeness/formality with their conversation partner. The overall decreased number of NTRI suggests that improvements on the SA students’ abilities to effectively relating themselves and valuing others (i.e., Savoir etre). Furthermore, Anna, Cathy, Bobby, and Isabelle, who used IfSS-PFs inappropriately in high-addressee awareness situations before this SA sojourn, no longer used such IfSS-PFs upon their returns. For example, Isabelle was able to self-correct her inappropriate use of IfSS-PFs without negatively affecting the flow of the conversation in the post-SA interview, which also demonstrated that she “can identify causes of misunderstanding… and dysfunctions” (Byram, 2012).

Regarding the use of DtSS-PF, the participants began using them more actively to express their affective stances in the post-SA interviews than in the pre-SA interviews. For example, most of the DtSS-PFs were soliloquy-like utterances (e.g., recalling and exclamatory) and were used without any sentence-final particles (SFP) in the pre-SA interviews. However, they began using DtSS-PFs more actively with appropriate SFP to express their affective stances, to co-construct ideas with the interviewer, and to provide background information to show the active engagement more clearly.

There were also haphazard changes and individual differences in the SA students’ speech styles and style-shifting development, such as the use of nan to/te iu [what was it call?] for recalling information in post-SA interviews. There are two potential explanations for this change: negative L1 transfer or incomplete utterance of nan te iu n dakke, which L1 speakers often use for recalling. With regard to negative L1 transfer, in English, What is it called? is often used as a soliloquy-like utterance for recalling information. In this case, the change is considered a regression instead of an improvement because it indicates that a speaker has relied on an English direct translation, which does not fully function the same way that the Japanese version does. With regard to the utterance of nan te iu n da kke [I wonder what it was call (I wonder how I say it)], a learner might have heard Japanese L1 speakers use the phrase often enough to have begun incorporating it in their own speech, but they might still have lacked the linguistic skills to produce the correct version of the phrase.

When comparing the current findings with L1 speakers’ masu-form uses from the previous studies, the masu-form uses of the participants in the current study are still more abundant (72.1%) after SA sojourns than were Masuda’s L1 speakers (52.5%) and those in Okazaki’s study (69%). However, the acquisition of L1 norms is not the goal of ICC; rather, it focuses on the skills that enable FL learners to communicate effectively and appropriately in the target language. The changes in the participants’ speech style in the current study, especially their plain-form choices, suggest that their development in ICC by utilizing speech-style shifting in Japanese.

The findings also suggest that the development of an effective and appropriate speech shift is not simple and that it depends on several factors. To develop similar skills—when and how they become aware of speech styles choices as a way of indexically defining a context, a relationship, and so on—L1 speakers of Japanese begin very early and develop competence over many years. This notion of taking extensive time to master such skills suggests that such skills need to be addressed prior to SA programs for SA participants to take full advantage of the SA learning environment.

To facilitate SA students’ style-shifting development, formal instruction at home institutions should focus more on two different forms (masu form and plain form) and two different plain-form usages (informal and detached) by providing explicit instructions and feedback on how they are used and what effect they have in a conversation. As application exercises, instructors can use textbook dialogues that students have already learned. For example, if students have already learned a conversation between a teacher and a student in masu forms, an instructor can set up a different context, one in which two friends perform the same conversation in plain forms, and have students discuss what kinds of changes they should make for the new context. After that discussion, students can practice the conversation with classmates. Fantini (2009) stated that it is challenging for educators to help learners recognize their etic stance while attempting to uncover the emic viewpoint of their hosts, assuming adequate motivation, interest, willingness, and contact. However, by continuing this exercise for each dialogue, students start to pay more attention to the relationships with their interlocutor and use two speech style appropriately.

It is also important to gradually explain the concept of “low-/high-addressee awareness” when practicing two different speech styles in Japanese. In a beginning-level class, an instructor should focus on providing explicit feedback on the wrong use of plain form in high-address-awareness situations in masu-form predominant contexts because such use of plain forms can be considered impolite by their interlocutor. In advanced classrooms, learners should focus on the use of plain forms in low-addresses awareness situations in masu-form predominant contexts so that they can effectively and appropriately adjust their speech style to suit their identity while constructing a desirable relationship with the interlocutor. (Interested readers can refer to Taguchi & Yoshimi (2019), who discussed in detail effective instructional practices that might enhance learners’ skills in Japanese style-shifting.)

The current research included some limitations. First, using the OPI format to collect the participants’ data may have limited the ability to measure some crucial skills of ICC. For example, because it was an interview format, most of the participants’ utterances were responses to the interviewer’s questions, which made it difficult to measure other aspects of the participants’ communication skills, such as their skills as listeners (e.g., aizuchi), as discussed in Ikuta’s study (1983; 2008). Furthermore, as Zeng (2015; 2018) has noted, some of the techniques used in OPIs might not reflect real communication, because the interviewer has a set agenda to measure the interviewee’s oral skills based on the descriptions of the OPI scale. Such an agenda (i.e., measuring the interviewee’s oral skills) rarely occurs in daily communication. Because style shifting is primarily done to make communication go smoothly (e.g., to avoid sounding either unfriendly or too friendly or to help the interlocutor to complete a sentence), using natural conversation as data would have provided better insights into ICC than using the OPI format. Second, the judgment of IfSS-PF or DtSS-PF was done mostly by me based on the findings from previous research on L1 speakers’ style shifting. However, my being a Japanese instructor and older than my college-age participant may have resulted in conversations that did not reflect younger generations’ perceptions of speech-style norms.

Future research should, therefore, collect natural conversation data, both informal and formal, to examine style-shifting development at different periods. Having both informal and formal conversation data will enable researchers to assess learners’ style-shifting development from different angles to capture the whole picture of style-shifting development in real-world communication. In addition, data on stimulated recall can be used to obtain SA students’ perspectives on changes in speech style. Such data could provide us better insights into Emma’s haphazard change from an appropriate use of DfSS-PF nan da kke, to inappropriate use of IfSS-PF nan to iu for recalling information. Finally, a longer-term study could reveal a whole picture of ICC development.

Conclusion

This study aimed to demonstrate how examination of Japanese speech style shifting can be used to measure SA students’ ICC development. Although there were individual differences observed among the participants, the overall findings suggest that participants learned how to sound more approachable while still maintaining the appropriate level of politeness, which suggests ICC development enabled them to communicate effectively and appropriately in intercultural interactions.

Style shifting is not limited to the Japanese spoken language; all spoken languages have stylistic variations (e.g., regional and social dialects, registers, and formalities), and a speaker uses more than a single speech style to communicate effectively and appropriately in different contexts. Although the types of linguistic, sociolinguistic, and discourse competencies are different, examining style-shifting development can be used as a measurement of FL learners’ ICC development of other languages. If indeed one aim of foreign language education is to cultivate and nurture students’ ability that artificial intelligence does not have and to equip them for the complex demands of the future workforce, it becomes imperative for future research to place greater emphasis on verbal and behavioral outcomes of students’ ICC development.

References

ACTFL. (2012). ACTFL Proficiency Guidelines 2012. (June 4, 2023) https://www.actfl.org/publications/guidelines-and-manuals/actfl-proficiency-guidelines-2012

Baker-Smemoe, W., Dewey, D. P., Bown, J., & Martinsen, R. A. (2014). Variables Affecting L2 Gains During Study Abroad. Foreign Language Annals, 47(3), 464-486

Barili, A., & Byram, M. (2021). Teaching Intercultural Citizenship Through intercultural service learning in world language education. Foreign Language Annals, 54, 776–799.

Bennett, T. (2009). A Study of the Management Leadership Style Preferred by it Subordinates. Journal of Organizational Culture, Communication, and Conflict, 13(2), 1-25.

Burns, P D. (1996) Foreign Students in Japan: A Qualitative Study of Interpersonal Relations Between North American University Exchange Students and Their Japanese Hosts. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

Byram, M. (1997). Teaching and Assessing Intercultural Communicative Competence. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Byram, M. (2008). From Foreign Language Education to Education for Intercultural Citizenship: Essays and Reflections. Bristol, Blue Ridge Summit: Multilingual Matters.

Byram, M. (2012). Conceptualizing Intercultural (Communicative) Competence and Intercultural Citizenship. In J. Jackson (Ed.), The Routledge Handbook of Language and Intercultural communication (pp. 85–98). Abingdon: Routledge.

Byram, M. & Wagner, M. (2018). Making a Difference: Language Education for Intercultural and International Dialogue. Foreign Language Annals, 51(1), 140–151.

Chen, G. M., & Starosta, W. J. (1996). Intercultural Communication Competence: A Synthesis. Annals of the International Communication Association, 19(1), 353–383.

Cook, Haruko M. (2006). Japanese Politeness as an Interactional Achievement: Academic Consultation Sessions in Japanese Universities. Multilingual 25, 269–292.

Cook, Haruko M., (2008). Construction of Speech Styles: The Case of Japanese Naked Plain Form. In Mori, J & Ohta, A. (Eds). Japanese Applied Linguistics, (pp. 80-108). Continuum.

Cook, H. (2016). 6. Adult L2 learners’ acquisition of style shift: The masu and plain forms. In M. Minami (Ed.), Handbook of Japanese Applied Linguistics (pp. 151-174). Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter Mouton.

Deardorff, D. K. (2006). Identification and Assessment of Intercultural Competence as a Student Outcome of Internationalization. Journal of Studies in International Education, 10(3), 241-266.

Deardorff, & Jones, E. (2012). Intercultural Competence: An Emerging Focus in International Higher Education. In Deardorff, H. de Wit, J. Heyl, & T. Adams, (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of International Higher Education (pp. 283–303). Sage.

Fantini, A. (2009). Assessing Intercultural Competence: Issues and Tools. In D. K. Deardorff (Ed.), The SAGE Handbook of Intercultural Competence. (pp. 456 476). Sage.

Fantini, A. (2019) Intercultural Communicative Competence: A Multinational Perspective. New York, NY: Routledge.

Hill, I. (2006). Student Types, School Types and Their Combined Influence on the Development of Intercultural Understanding. Journal of Research in International Education, 5(1), 5–33.

Hymes, D. (1964). Language in Culture and Society: A Reader in Linguistics and Anthropology. New York: Harper & Row.

Ikuta, S. (1983). Speech Level Shift and Conversational Strategy in Japanese Discourse. Language Sciences, 5(1), 37-53.

Ikuta, S. (2008). Speech Style Shift as an Interactional Discourse Strategy: The Use and Non-Use of desu/-masu in Japanese Conversational Interviews*. In Jones, K., & Ono, T. (Eds). Style Shifting in Japanese, (pp. 9-38). John Benjamins Pub.

Itani, R (1992). Japanese Conjunction Kedo in Utterance-final Use: A Relevance-based Analysis. English Linguistics, 9, 265-283.

Iwasaki, N. (2008). Style Shifts Among Japanese Learners Before and After Study Abroad in Japan: Becoming Active Social Agents in Japanese. Applied Linguistics, 31(1), 45-71.

Iwasaki, N. (2011). Learning L2 Japanese “Politeness” and “Impoliteness”: Young American Men’s Dilemmas During Studying Abroad. Japanese Language and Literature, 45(1), 67-106.

Izuhara, E (2003). Shuujoshi ‘yo’ ‘yone’, ‘ne’ Saikoo [The sentence-final particles yo, yone, and ne revisited]. The Journal of Aichi Gakuin University 51, 1-15.

Jian, X. (2021). Negotiating a Co-constructed Multilingual and Transcultural Third Space. In X. Zhang, and X. Jian (Ed.), The Third Space and Chinese Language Pedagogy, 7-25. London: Routledge.

Jorden, E. & Noda, M. (1987). Japanese: The Spoken Language. Yale University Press.

Kasper, G. & K. R. Rose. (2002) Pragmatic Development in a Second Language. Blackwell Publishing.

Kelley, C., & Meyers, J. (1995). The Cross-cultural Adaptability Inventory. Minneapolis, MN: National Computer Systems.

Kramsch, C. (2009). The Multilingual Subject. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Koester, J., & Olebe, M. (1988). The Behavioral Assessment Scale for Intercultural Communication Effectiveness. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 12(3), 233–246.

Lee, J. & Song, J. (2019). Developing Intercultural Competence through Study Abroad, Telecollaboration, and On-campus Language Study, Language Learning & Technology, 23(3), 178-198

Makino, S. (2002). When Does Communication Turn Mentally Inward? A Case Study of Japanese Formal-to-Informal Switching. In Akatsuka, N., & Strauss, S. (Eds.), Japanese/Korean Linguistics 10. CSLI, Stanford, 121–135.

Masuda, K. (2010). Nihongo gakusyuu-sya no buntai sifuto ni tsuite. [Japanese foreign langauge learners’ style shifting] In Minami, M. (Ed.) Gengo-gaku to Nihongo-kyooiku no Tenkai to Hyousiki VI, [Linguistics and Japanese Language Education] (pp.191-212). Tokyo: Kuroshio Syuppan. [Kuroshio Publishing]

Maynard, S. K. (1993). Discourse Modality: Subjectivity, Emotion, and Voice in the Japanese Language. John Benjamins.

Moody, S. J. (2018). Fitting in or Standing out? A Conflict of Belonging and Identity in Intercultural Polite Talk at Work. Applied Linguistics 39(6), 1–25.

Moody, S. J. (2019). Interculturality as Social Capital at Work: The Case of Disagreements in American-Japanese Interaction. Language in Society 48(3), 377 402.

Munezane, Y. (2019). A New Model of Intercultural Communicative Competence: Bridging Language Classrooms and Intercultural Communicative Contexts. Studies in Higher Education, 46(8).

Ohori, T. (1996). Remarks on suspended clauses: A contribution to Japanese phraseology. Pragmatics and beyond. New Series, 32, 201-218.

Okamoto, S. (1999). Situated Politeness: Manipulating Honorific and Non-Honorific Expressions in Japanese Conversations. Pragmatics, 9(1), 51-74.

Okazaki, W. (2015). Style Shift to Plain Form in Advanced Learners of Japanese: Focusing on Informal-Style. Bulletin of the Graduate School of Education, Hiroshima University. Part. II, Arts and Science Education, 64,147-156.

Perry, L. B. & Southwell, L. (2011). Developing intercultural understanding and skills: models and approaches. Intercultural Education, 22(6), 453–466.

Portalla, T., & Chen, M. (2010). The Development and Validation of the Intercultural Effectiveness Scale. Intercultural Communication Studies, 3, 21-37.

Siegal, M. (1995). Individual Differences and Study Abroad: Women Learning Japanese in Japan. In B. F. Freed (Ed.), Second Language Acquisition in a Study Abroad Context. (pp. 225-244). John Benjamins.

Taguchi, N. (2009). Pragmatic Competence. Berlin, New York: De Gruyter Mouton. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110218558

Taguchi, N. (2015). Developing Interactional Competence in a Japanese Study Abroad Context. Multilingual Matters.

Taguchi, N. & Collentine, J. (2018). Language Learning in a Study-Abroad Context: Research Agenda. Language Teaching, 51(4), 553–566. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444818000265.

Taguchi, & Yoshimi, D. R. (2019). Developing and Teaching Interactional Competence in Japanese Style Shifting. In Teaching and Testing L2 Interactional Competence (1st ed., pp. 167–191). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315177021-7.

Tran, T. Q., & Duong, T. M. (2018). The effectiveness of the intercultural language communicative teaching model for EFL learners. Asian-Pacific Journal of Second and Foreign Language Education, 3(1), 1-17.

Tobaru, H. (2019). Understanding the Difficulties in Building Intercultural Relationships from Perspectives of American Students and Japanese Students during a Short-term Study Abroad in Japan, Journal of the National Council of Less Commonly Taught Languages, 25(1), 109-131.

van Berg et al., Connor-Linton, J. & Paige, M. R. (2009). The Georgetown Consortium Project: Interventions for Student Learning Abroad. Frontiers: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Study Abroad, 3, 1-48.

Walker, G. & Noda M. (2010). Remembering the future: Compiling knowledge of another culture. In G. Walker (Ed.), The Pedagogy of Performing Another Culture (pp. 22-50). Columbus, OH: National East Asian Languages Resource Center.

Zhang, X. & Jian, X. (2021). Co-constructing the Third Space: Negotiating Intentions and Expectations in Another Culture. London: Routledge.

Zeng, Z. (2015). Demonstrating and Evaluating Expertise in Communicating in Chinese as a Foreign Language. Doctoral dissertation. https://etd.ohiolink.edu/

Zeng, Z. (2018). Striving for The Third Space: An American Professional’s Unconventional Language Use in Chinese Workplace. Foreign Language Annals, 56, 58-683.

Zeng, Z. (2021). Constructing Self in the Third Space: Negotiating Expertise in Globalized Workplaces. In Zhang Xin, and Xiao Jian (Eds). The Third Space and Chinese Language Pedagogy, 68-98. London: Routledge.

Appendix

Abbreviations used in morpheme-by-morpheme glosses